This apparently simple and rather serene painting is, like many other Bosch works, carefully divided into realms of influence and action, which in this case may not be obvious at first glance.

The Adoration's realm of action is capped by five angels. Occupying the space of intersection between the heavenly and earthly realms, the angels are not exclusively clad in the spiritual pink we might expect; yet all but one of them (the diminutive figure on the left) sport it, whether in their wings or garments. They are touching the earthly realm and, like the divine influences in contact with the mortal realm in the Garden, the pink has become tinged with red.

Bosch introduces the use of substantial gilded areas here to indicate both higher spiritual values and the element air (see the reason for this interpretation below, in the discussion of the second magus' gift.) The varying colors of garment and wings indicate orders of angels. The group as a whole represents the heavenly host. What may be an archangel clad in gold presides over the greatest remaining portion of the castle, occupying the left side of the painting. Overall, the arrangement suggests a Swedenborgian assortment of angels from different levels of heaven; unsurprising, since visual evidence suggests that Bosch's inner revelations had a great deal in common with Swedenborg's.

The angels are spreading a green canopy over the affair because (when not applying it to foliage, where it represents the fecundity of life), when employing it as a symbolic element, Bosch uses variations of the color green to indicate the best that can be achieved under earthly circumstances. (See the analyses of the parrots in the Garden of Earthly Delights, center panel slides 42 and 43, for an explanation of this.) In both this painting and Death and the Miser, it's used for the robes of the pentitent.

As we go forward, let's remember that the castle, or temple, represents man's inner life: the house he lives in, spiritually speaking. It ought to be filled with God's divine spirirt, but is empty.

The central region of the landscape reveals a pastoral scene behind the decaying walls of the castle.

In the distant background lies the motif of a mystical city representing the New Jerusalem.

We know the city is meant to represent a unique city because of the massive scale of the cathedrals, especially the one to the right. Both spires eclipse the size of the city gates, implying architecture on a scale that well exceeds the engineering capabilities of Bosch's times.

Although the countryside is pastoral, armies are still in action, patrolling, ever vigilant against the forces of evil.

In the right hand side of the landscape, two lovers stroll across a bridge, indicating the virtues of heavenly love. Like many of Bosch's vignettes from the Garden, tossed off almost effortlessly as adjuncts to his central theme, this touching image is a whole painting in itself. Note the cross on the right, indicating Christ's presence as a natural element of the landscape. It's tiny details like this that remind us of how thoroughly Bosch attended to his works. There is much more to this scene, however, than meets the eye; and we'll get to that.

The empty space spanning the area between the castle walls represents the prechristian era; a ruined entity, with religion almost entirely devoid of the reverence and worship which ought rightly to inhabit it. It also represents our own inner emptiness.

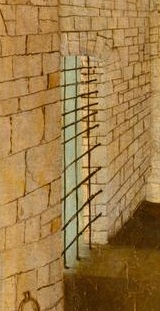

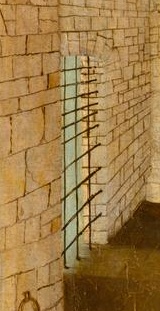

To emphasize the fact that knowledge of God's kingdom is closed to mankind, Bosch has gone so far as to bar the entrance on the left—a space that seems clearly, at one time, to have provided access to the temple. The significance of this will become more evident.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

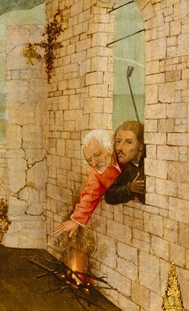

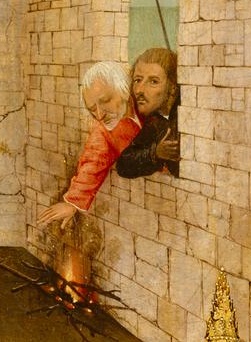

| To be sure, the space is pregnant with potential, as the bird's nest and vegetation indicate; and it is not entirely forgotten or useless. The two men (who are actually one, as we shall see) on the right hand side warm themselves over a scant fire of sticks. Above them, two bars, which indicate that this entrance, too, was barred at one time. They seek whatever access they may gain to what little of God's flame still remains alight in this empty temple. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The central portion of the painting is dominated by the Virgin and Christ Child. Seated on a cloth of gold, she is poised on an expensive cushion better than one generally finds in mangers.

The Mary we see here, serene and unperturbable, bears tresses identical to Eve's in the Garden: she is, symbolically, the same woman: the essential woman, womanhood itself.

The perfection of her tresses, shining with the reflected golden light of God's Grace, offers us womanhood untouched by mortal sin. She offers a stunning contrast in simplicity to the baroque finery of the Magi, indicating her inherent simplicity, and renunciation of both mortal and venial sinfulness. Her austerity does not admit even the possibility of corruption.

Christ's hands are spread in a mudra of confidence, as though he already knows he is master of this world, despite the opulent costumes and rich trappings of his visitors. This Christ child is, in other words, nothing like the corpulent infants grasping at breasts we see in other versions of the madonna and Child. It's deftly understated, so subtle it's nearly unnoticeable. Yet Bosch has ingeniously given us a remarkable and highly original image: a Christ child who is actively and truly embodying an authority which extends far beyond the fact of His infancy. Despite His tiny size, He is in charge of the events here.

In order to better understand Bosch's overall intentions, one must see that the painting creates a circle of divine influence. This device, as we shall see, is an ingenious recreation of the tantric circle in the Garden.

In tantric art, the world typically revolves around a central sacred image which influences everything around it. Bosch, who employed this to extraordinary effect in the Garden, has not only re-created, but reinvented this device for this painting.

The circle of divine influence is, like that of the Garden, a progressive movement from the earthly, or natural, side of spiritual development into the spiritual realm. This movement and its specific inner meaning is also a defining feature of Gurdjieff's enneagram— and, of course, Swedenborg's cosmology.

As with the enneagram, Bosch's circle contains nine positions; and each one can be interpreted as exerting an influence belonging to its own position. (There is nothing, perhaps, particularly surprising in this arrangement; ninefold iterations of divine influences stretch all the way from the levels of heaven and hell in Dante's Divine Comedy to the Memphite Theology of Egypt's 25th dynasty, circa 700 BC or earlier.)

The movement begins at the 12 o'clock position above Mary and the Christ child. In this position, we see the opening through the castle walls that leads into the landscape where the new Jerusalem is located. It represents the higher influences of heaven as incorporated at the top of the painting.

Immediately to the right, in approximately the 1 o'clock position, we encounter two rather ordinary men reaching for the flame of God within the ruined castle. This is the initial effort of the ordinary man towards Grace; his first inkling that there is an inner state he must reach towards. Take note that these two figures actually represent one man, in two stages of his life; and they represent the element earth, or, the material incarnation of man.

Continuing our journey, we encounter the three wise men. We might expect them to have exemplary spiritual qualities on display; but the lesson here is that even though they are wise men, they haven't yet been informed by the Spirit of Christ. They can't be, of course; they appear at the beginning of Christ's passion, not during the middle years of His teaching, or the culmination of His life and work. Each one of them represents a sincere, yet distinctly worldly, effort to relate to Christ's presence. And each one of them represents a progressive step closer and closer to the attitude that is necessary in order to submit to God.

In order to understand this, we need to examine the figures in much greater detail.

There is even a message in the headgear of the three wise men. The first one wears an exaggerated turban and a crown; the second one has a smaller, less overstated single crown; and the third one's crown, although very elaborate, has been taken off and is on the ground. Taken together, the three pieces of headgear represent progressive stages in submission to Christ. hence the first wise man sees himself as the most important; the third, the least.

The headgear of the third wise man is amply adorned with pearls, or lies, but he has put them aside, and bared his head, implying that he has finally understood how he lies to himself.

It's worth a moment to reflect on how thoroughly Bosch has managed to confound our expectations here. Rather than depicting the three kings as important personages, he has assigned them positions in the scale of inner development which are lower than the homespun hermit that follows them in the progression. They're bit players, minor notes in the scale of Being: here, their royalty is a liability, not an asset. Because they're accustomed to ruling themselves, they don't know how to submit; and here, in the presence and authority of Christ, submission is paramount.

If we understand the subtle arrangement of figures around the Madonna and Child, we see that Bosch is telling us that all the trappings of royalty and all worldly success take place at relatively low rungs on the ladder; the achievements, status, power and wealth these men have is not enough to qualify them for an inner search, earnest though their aspirations may be. The artist has skillfully managed to hide this truth in plain sight.

It's worthwhile to compare this figure to the miser in Death and the Miser. Both figures wear similar garb, are stooped in submissive postures, carry canes indicating their inner acknowledgement of spiritual weakness, and serve similar purposes: both of them indicate a man of inner qualities who has recognized his failings, and is actively engaged in an inner spiritual pilgrimage.

How Bosch managed to pull this little personal joke off in the middle of this very serious and religiously adept painting is a question. It takes a peculiar and perverse kind of genius to manage to be both deeply religious and humorous at the same time. Bosch, however, was never above having a little fun in the midst of serious questions, which is a testament to his own inner mastery.

So from this position, moving around the circle, the viewer is forced to default back to the Virgin and Christ. We are deflected back into the center of the circle, which represents the only passage towards God: we're being told that the spiritual passage does not consist of a voyage around the periphery of the circle, that is, the path itself, but rather a journey into the heart—the center of the circle. And this is exactly the message we would expect from the master of a school centered around Christ and the Virgin.

We've passed over a few elements which still need to be dealt with here, notably the left side of the painting.

The owl, representing divine wisdom, is a subtle but recurring figure who supervises sacred activities, a tiny observer that dwells within the inner self of the soul, keeping an eye on things. Friendly, nonjudgmental, and always seeing what takes place, the owl is a symbol of the kind of self-observation that Bosch encourages us all to undertake in our spiritual effort. Bosch consistently included tiny owls in the paintings that encode wisdom teachings. Generally speaking, paintings without the owl are either not from the school of Bosch, or were merely commercial works. The owl, like many of the other icons and motifs Bosch employs throughout his ouevre, always signifies when he appears.

Summarizing the spiritual path that the artist lays out on the Tantric Circle, we are given a progression of stages through which a man must go in order to submit to God and discover the nature of his inner Being.

In youth, a man professes faith. In old age, he seeks it. (The two men in the window.)

The moment that he begins to acquire a sense of inner work, first, he thinks it is about himself. (The magus facing the viewer)

In the third stage, he believes he is important and wants God to recognize him. (The black magus.)

Next, he finally realizes submission is necessary. (The kneeling magus)

Then his real search begins, acquiring a sense of urgency, or will. (the hound)

He acquires a sense of humility and servitude (the kneeling hermit.)

Then he undergoes a ritual of sacrifice and purification to make himself acceptable to God. (The bull.)

Finally, he discovers that his way is still barred, and the only path to God is through Christ.

The practice circulates around the heart of Christ, symbolized by the Virgin Mary and Christ Himself. In a like manner to the motif of the lock in Death and the Miser, life circulates around the central influence of the holy Trinity.

Readers should refer to the second page on this painting for a more detailed discussion of the background.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||