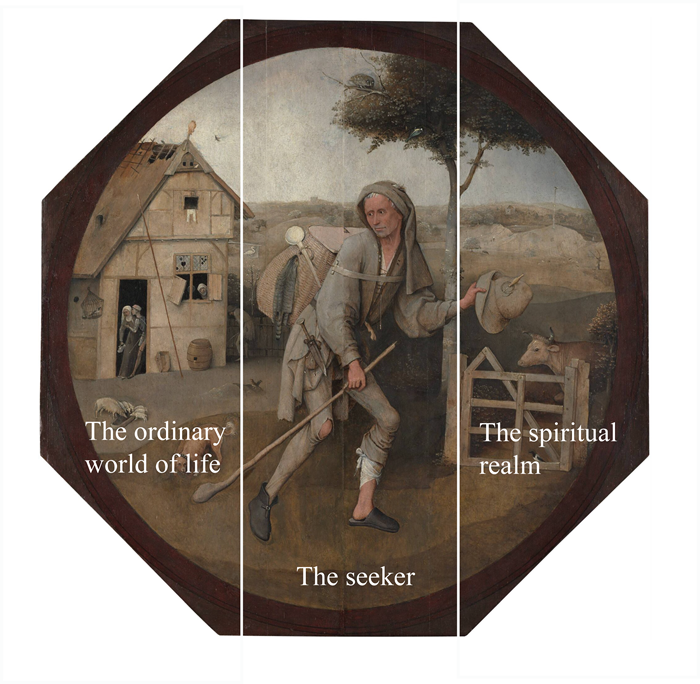

Zen master Dogen referred to his beginning pupils, monks on the path, as "leavers of home." The term, in Zen, actually has a specific meaning, since it's the first step on a sixfold path that progresses from leavers of home to patch-robed monks, and then to aspirants having the flesh, blood, bones, or marrow of the teaching. Each stage represents a progressive understanding of the spiritual path, very much like what's depicted in Bosch's The Adoration of the Magi.

Although the iconographies are widely divergent, the essential principles are exactly the same: a man passes through an indentifiable series of stages in inner development, each of which is known; these are the qualities that take the measurement of who a man is, in an inner sense.

These qualities are reflected in how he appears and behaves outwardly; and this principle of the outer being a reflection of the inner quality—an essential doctrine of Swedenborg's—comes into play as we consider the strong connections between Bosch's works and the famous Middle German folk figure Till Eulenspiegel, whose presence is tangible in most of Bosch's great paintings. Eulenspiegel and Mullah Nassr Eddin (see below) represent early traditional versions of "crazy masters," the most recent example of which was the 20th century Tibetan master Chögyam Trungpa. (Some argue that Gurdjieff also fell into this category.)

It may at first glance seem absurd to refer phrases drawn from Zen practice to a Northern Renaissance painting, but the ideas behind such practice are emphatically universal; and in this instance, the comparison is entirely appropriate, because Bosch has gone out of his way to construct a carefully considered allegory of the idea of a man setting out on the path to spiritual discovery: a "leaver of home" in the true esoteric sense of the word.

As in all of Bosch's best paintings, the picture—as simple as it appears to be—is a narrative with a distinct flow and a story to be told.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Images of this kind leave us with little doubt that much of Bosch's humor is inspired by the traditional middle German folk hero Till Eulenspiegel. Eulenspiegel means "owl-mirror" in German, that is, a reflected image in which we discover a higher form of wisdom. The implication is that the owl sees himself — that is, discovers his own wisdom through the recognition of his own image, in other words, self-remembering.

The lurking owls in nearly every one of Bosch's paintings are a direct reference to the higher consciousness and awareness embodied by this folk hero's seemingly ridiculous actions; and his indisputable connection to the Sufi folk hero Mullah Nassr Eddin, a particular favorite of Gurdjieff's, links into a long-standing tradition of esoteric knowledge expounded by seemingly foolish actions and people. Bosch's irreverent and bizarre sense of humor finds a comfortable and completely traditional home here, placing it firmly in the realm of teaching, rather than tomfoolery.

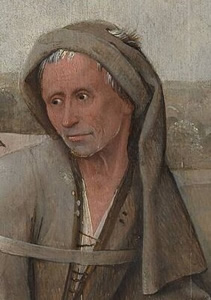

Our traveler cuts a rather dashing figure despite the apparent poverty of his circumstances and garb. Caught mid-stride, we're left with no doubt that he is on his way.

To be sure, despite his average appearance, this is no ordinary traveler, beginning with his kit. He is prepared; he has carefully provisioned himself with the essential tools for an inner search.

The spoon above the cat indicates that he knows how to feed himself. This is important in light of the fact that the swine back at the inn face an empty trough. Our traveler, on the other hand, is properly equipped to acquire the sustenance he needs during his journey.

The wicker basket serves multiple symbolic purposes. First of all, it indicates that our seeker has not yet unburdened himself of worldly baggage and concerns; he is not only weighed down by them, the strap across his chest tells us that he is also restrained by them; and this clever device serves to hold him back visually, indicating that his literal attachment to worldly concerns will hinder him on his journey. The picture is, in other words, a realistic assessment of a man just setting out on his search for his inner self.

Our leaver of home also carries a dagger with him. While we might expect any traveler to carry a defensive weapon, the dagger is in fact to all appearances the exact same dagger used to prop open the lid of the trunk representing the inner self in Death and the Miser. A close look at the identical and distinctive hilts confirms this; and since the painting is surmised to have originally formed part of a diptych or triptych with the Miser panel, the hypothesis that the dagger connects both the symbolic meanings and the two principle figures of the paintings becomes a powerful one... "same sword, same man." Both daggers, furthermore, are deployed in direct proximity to bags of money, underscoring their symbolic relationship.

The dagger represents a cutting tool, a device that can discriminate, opening the contents of a man's inner life and exposing it for examination. The bags of money represent wealth- whether worldy or inner, the implications are the same. The difference here is that our wayfarer (the younger version of the miser languishing on his deathbed) has his inner wealth, his purse, dangling from the outside of his garments, an exposed place where a cutpurse might easily make off with it. Our "miser," on the other hand, has his inner wealth firmly stored in a sturdy trunk.

Here, at once in a single figure, we have a combination of three key stages of the inner search from the Adoration; the doffed hat, the hound that seeks Christ, and the headgear of the penitent hermit.

The combination locates the seeker's spiritual aspirations and accomplishments somewhere at the base of the tantric circle of development we see in the Adoration, implying a versatility that has prepared him for the next stage: atonement and sacrifice, in the form of the bull.

Moving into the sparesely decorated right hand portion of the painting, Bosch intentionally depopulates the visual field. Our seeker is, after all, moving into the unknown; and the less definitions Bosch gives us here, the better.

There are several important clues to what is going on, however, and one of them crops up in the tree above the action, not far from our little friend the owl. It's a sneaky little detail: and one has to have poured over Bosch at length, and in detail, to understand just what he's done here.

Here we find a chickadee (left), in the same position as the exact same bird in the Garden of Earthly Delights (right). Since Bosch employs a consistent symbolic vocabulary, we can be sure that this bird conveys a symbolic meaning directly related to the bird in the Garden.

The bird in the Garden, depicted as an oversized creature of the imagination, represents a superstitious or imaginary belief in God and the afterlife. (see the slide show commentary on the garden of earthly delights, center panel, slide # 97.) Shown here in life size, it represents an actual belief, that is, a belief based not on imagination, but a real inner understanding. Rather than hanging from a bone-dry, thorny branch, representing barren ideas, it hangs from verdant greenery, that is, the ideas that support it are alive and growing.

To the right of our seeker lies a stile with a bull. The bull, representing Luke the evangelist and the atonement and sacrifice of Christ, is an indication of the path the seeker is on. He is destined to purify himself through suffering; but he isn't at that stage yet. A gate lies between him and that possibility. Like the miser's trunk, the gate is prominently marked with the sign of the Holy Trinity in the form of a triangle in the top left corner. The right-hand timber of the triangle extends from the top to the bottom of the gate, symbolizing the fact that the Holy Trinity penetrates and influences all levels of effort one must pass through, from the top to the bottom.

This bull is the selfsame bull we find in the Adoration, located in the position on the path where sacrifice and purification is needed; and as is usually the case with Bosch, the symbol is applied consistently, with the same general meaning in both pieces.

And in a final example of attention to detail and symbolism, the caged bird on the left hand side of the painting turns up here on the right side, free and uncaged:

In summary, Bosch hasn't left any doubt as to what his meaning is here: a deft and intriguing summary of a seeker setting out on the path to inner truth.

Assuming this painting was, indeed, part of a larger whole of which the Death and the Miser formed another part, it appears to be the keynote piece of a whole work consisting of an allegory about man's inner search, and his passage through life. In that case, we can hypothesize that Death and the Miser is the final chapter in that story, and that the man we see here is, in fact, a younger version of the Miser himself.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||