The Esoteric Bosch

Metaphors for Man's Inner Life

in The Garden of Earthly Delights

In a painting which depicts the intersection between divine and natural influences,

it should be no surprise to find that man is swallowed by earthly things.

The Language of Esotericism

The many different interpretations of this painting over the centuries have focused on a wide variety of analyses of the various social and religious influences that were current in and around Bosch's geography and times, with attempts to fit his extraordinary painting into multiple academically justifiable contexts. But this may not be necessary; the painting is, after all, clearly and unambiguously about the influence of divinity upon the earth, and the actions of man. Although we will say it, it simply goes without saying that the painting has esoteric content, which means, comment that cannot be understood right off the bat, or obviously.

Besides this, we do not just need a scholarly interpretation of this painting; we need a human one, because the painting is about human beings and their nature. It is not meant to speak to some obscure part of mankind, some secret group; it is meant to speak to everyone. And it must do so in a language that is not too complicated to understand. The ideas in it should be simple, compelling, and raise questions about who we are and what we are doing, just as the painting does.

So if the painting has esoteric content, why not offer an esoteric explanation—not meaning obscure or secretive, but an inner explanation? An explanation that examines what it says about the inner life of man.

Esoteric mysticism, while it has undergone many convolutions and evolutions over the centuries, emerges from the 13th century sharing a common language and set of concepts that can be mutually sourced and traced to a set of influences and threads that runs through the late Middle Ages in Europe and the Middle East.

Specific sources such as Ibn 'Arabi and Meister Eckhart, who shared identifiable commonalities in their not-so-esoteric (yet profoundly esoteric, in the sense of divinely influenced, or inner) writings, had already left a definite mark within the esoteric religious practices of the late 1400s. And many of the ideas about man's nature that these two extraordinary religious figures and philosophers explored were in fact quite ancient ones, with roots in Platonism, Zoroastrianism, and other earlier practices.

The esoteric influences in Renaissance Europe are, in fact, far too many to mention; and so, instead of attempting to define Hieronymus Bosch and his paintings in the narrow terms and confines of a specific sect and its ideas, it's worthwhile to try and examine his paintings from a generalized understanding of ideas about Divine influences, man, and his inner state.

It turns out that the vast majority of his painting can indeed be understood quite directly by applying this interpretive methodology; and many of the ideas he presents in the painting find powerful consonance in the ancient esoteric traditions, spread across a wide variety of religions and secret societies, that passed their knowledge and teachings down through generations, often directly within the inner circles of their own established and officially sanctioned religions. Meister Eckhart and Ibn 'Arabi stand out among all others as exemplary instances of this thread of esotericism; both offered teachings grounded in their own religions which reached out into extraordinary territory. They skirted the edge of heresy with their ideas; but they were so unusual and so amazing that in the end, no one dared to prosecute them for them, and instead, they became a part of accepted canon, although, to be sure, a canon of enlightenment that surpasses anything we could possibly call ordinary within Christianity or Islam.

Bosch did exactly the same thing in art. We will find that many esoteric ideas about man's nature are addressed in the painting; the symbolic language he uses shares much in common with the tradition of esotericism. There is no need to invoke a special secret sect of one kind or another, since many of the ideas he presents can be readily understood by anyone who has engaged in a personal search for enlightenment within the context of Jewish, Christian or Muslim mysticism. His peculiar use of devices that appear to derive from Buddhist Tantric art may even offer us an entreé to accessibility for the Eastern cultures, as well.

Perhaps the most misunderstood aspect of esoteric studies is that they are not, in the end, about being some special kind of secret elite. Esotericism is the study of man's inner nature — of a birthright which every human being ought to be interested in and study. The aim of esotericism is simple enough: to create, as Lord Pentland once said, a quality human being.

The overall loss of interest in this subject in the modern world has a great deal to do with the steady deterioration of man's external conditions.

The Painting

This is a painting that by its very nature creates and presents a koan, a Zen riddle that defeats rational attempts for interpretation — or, at least, superficially, it does so. The overall effect of the image is one that defeats the mind and its intellectual premises. We are presented with an impossible world, a fantastic world — yet it is, at the same time, a completely and utterly human world. The two qualities appear to contradict one another, and it is only in exploring and resolving the contradiction — which is a process, a movement through Being — that we can begin to gain any understanding of it. The painting has being, it contains questions about Being, and it moves us to a process of both Being and becoming. It does not, like many pieces of its period, present a didactic landscape with predictable illustrations of Bible stories or simplistic Christian renderings of sin, sacrifice, and redemption. It raises questions about the nature of consciousness itself; it investigates the effect of intelligence and conscious behavior in man on the influence of the divine. In this painting, the Divine arrives within earth and man, but is interfered with, and does not reach its proper expression. Yet the painting morphs into an extraordinary parable; by its very nature, it actually defeats the instrument that ultimately causes the damage it illustrates. This is a remarkable sleight-of-hand with few parallels in Western art.

Results of this kind are not obtained by accident. Bosch took great care to let us know that his painting is not meant to represent any objective, or outer, reality; in the process of doing so, he unveils a picture of man's collective unconscious and the inner processes that draw his spiritual nature away from the divine, and towards an engagement with the material.

What sets this painting apart from almost every other work of its time, or any time, is its otherworldliness. What Bosch meant to let us know is that our inner state is, indeed, otherworldly; it represents a different order of Being, one that stands between the divine and the material, and is informed on the one hand in the heavenly way by the divine, while being corrupted on the other hand by the earthly. The middle area of the picture in every panel represents the persistent and dynamic form of this interaction, in which the good is taken by the ordinary and the evil— absorbed, consumed—and turned to its own purposes. It's this steady degradation and deterioration of the sacred and the divine in the community of man that Bosch aims to represent for us.

What we are shown is the action of forces, or influences, upon man; and specifically, the action of these influences upon a man's inner life: the sensory and sensual contact that he has between the outer world and the divine influences that made him. These areas are realms of mysterious actions and enormous power. The forces are not physical forces; except in the right-hand panel, when we descend from Earth to Hell, the forces are all metaphysical, actions that lie within the realm of Being, and not material.

In the process of exploring this territory, Bosch uncovers— perhaps, we might even say, discovers —the inner, the secret, landscape in man which Carl Jung referred to as the collective unconscious; and indeed, the vista he presents us with spans the heavens, the vast distances of the planet itself, birth, life, and death. Compared to the art of his own century — compared to art of both earlier and later centuries — we see few intelligible points of contact. This is because the painting is informed not by intellect, like other Western art, but by real intelligence — an active force capable of questioning.

In order to explore the inner life, the inner space, of man, it was necessary to invent a new visual language, and the artist did so. Planning the painting and the intricate relationship of symbols must have taken years of introspection.

Many of the lessons of ancient esoteric schools informed his imagery; but he somehow managed to make it new, to reinvent it, to help us see it in completely new terms.

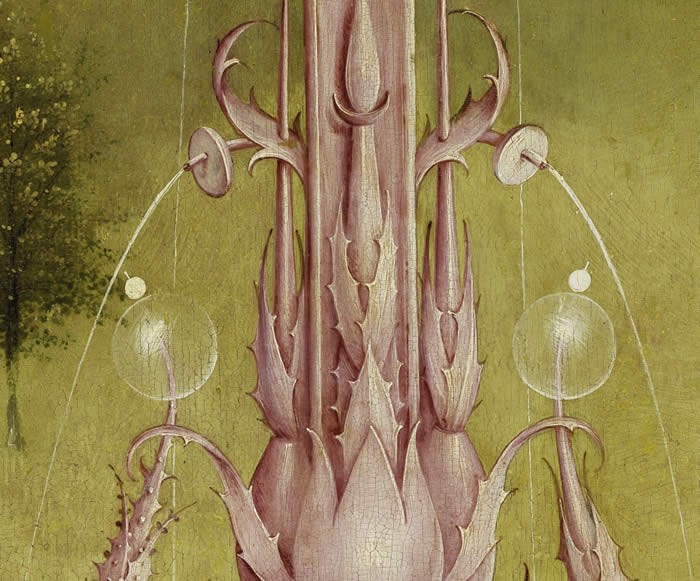

The idea, for example of alignment: that man has an inner structure, a vertical structure, and architectural symmetry and order to his inner state that ought to receive and express the divine. Ibn 'Arabi referred to this as the human kingdom, which, he indicated, ought to be under divine governance.

But how to express this visually? What would be an apparently possible task is almost effortlessly executed by our artist.

Not only does he manage to give us physical structures; pouring out heavenly waters, firmly rooted within the earthly sphere, they convey in every sense the glory, the dignity, and the perfection that ought to be present as a result of the influence of divinity.

A man ought to stand upright in himself, the artist says; and he gives us structures worthy of the concept.

The steadfast verticality of the divine fountains meets the (initially) unformed and uninformed horizontal influences of life, rooted in a bed of gems.

These gems represent man's birthright, all of the wisdom and intelligence which ought to be his by inspiration alone.

Yet the initial contact between the divine and the material already has corrupting influences. This metaphysical concept is depicted above Adam and Eve, showing that a fundamental change takes place between the transcendent and the immanent, before any human fall from Grace can be engineered. This philosophical proposition displays a sophistication well beyond the simplistic tale of the serpent and the apple tree. In the way the artist has depicted it— a peculiar and surreal combination of nature and then abstracted human face — we sense that the deviation from divine principles is both conceptual and material, a conundrum that informs the very root of the material world itself.

Transformation, we discover, is a tricky business; outcomes that should have been assured do not materialize. The lessening of vibration from higher to lower levels puts everything at risk.

In the chaos that ensues, despite the frenzy of sensuality, the artist

still somehow manages to confer a sympathetic dignity on the actions of man, as though, despite his yielding to temptation, all hope were not yet lost.

Yet in his center panel, the overwhelming force of sensuality proves to be too much of an attraction away from the divine influences that ought to inform his action.

The Tantric Circle

The action of the mind is ever present. In the central panel, it turns in a great circle, representing turning, ordinary (Gurdjieff would have called it associative) thought, and the action within a man as he moves towards the divine, away from the divine, sometimes even at the same time. His inner life is composed of a vast theater of characters, many different selves or "I's", each with his or her own inclination, temptations, and a narcissitic myopia that restricts their focus to a small group around them. This wheel of life, or Tantric Circle, becomes a processional that all of mankind participates in — yet it is in fact the center of each one of us, the way that our being is formed.

This absolutely extraordinary device, entirely without precedent in Western painting, incorporates a complex symbolism featuring a wide range of divine and profane animals, real and mythological, and a processional with mankind. The Tantric Circle reaches into the collective unconscious of mankind, emphasizing his connection with nature, but also evoking the many sacred symbols of higher levels which embody themselves in the animal world. The circle clearly evokes Swedenborg's later doctrine of correspondences, in which each material manifestation in the natural world expresses and corresponds to a quality of God; and it reminds us as well of mankind's diverse and ubiquitous religious roots, which reach back into pre-Christian time, and span global influences.

The artist, instead of limiting himself to the stock images of Christian divinity (the Virgin, Christ crucified, etc.) included ancient near and far eastern symbols such as the Brahma bull (evoking the Mithraic mysteries, Hindu cattle worship, and the Egyptian goddess Hathor; and the White Crane, a holy symbol in Japan and other Asian countries. A detailed treatment of the wide range of esoteric symbols in the circle can be seen in the slideshow on the center panel.

In the middle of the circle, an essential and feminine nature, set apart from the parade of external influences, still stands prepared to receive something divine — and it is waiting. The virgins carry white cranes on their head, indicating their willingness for God to come to them.

Bosch captures the question of an inner stillness, a place where the incessant movement of the self ceases; here, he has delineated in a visual sense between our spiritual center and the natural, or what Gurdjieff would have called essence and personality. He illustrates the union of inner opposites in this place, with black and white partners sharing moments of harmony; the spoon bills here still retain their divine quality and white coloration, and temptation, while still present, stands to one side.

One ghostly figure, the only such figure in the entire painting, alludes to the presence of the divine within the sacred center of man. This figure, which judged by its dress, its character, and its action, stands apart from everything else in the panel, and even the painting itself, represents a visitation by the Holy Spirit. it is meant to represent the inflow of God's influence into man — the thin, tenuous thread through which divine influence continues to inform the innermost part of man. The slender nature of this connection is indicated by this one tiny figure, in this landscape populated by hundreds.

Using deft, minimalist gestures, Bosch manages to convey questions about the inner life of man with this single figure. You'll notice that, although the figure represents a connection with God, no one is paying attention to her. All the parts of man that are meant to receive the presence of God are preoccupied, as though they had forgotten their purpose. They chat with one another, ignoring the very presence they are supposed to be awaiting. This is a commentary on our inner state: even the finest parts of ourselves—the ones who almost certainly ought to know better— have completely forgotten to attend to our responsibilities to God.

Bosch's ingenious deployment of oversized figures to represent figments of man's imagination is first used in this flock of birds, representing the world's religions.

Each one is a symbol or representative of divine influence, exaggerated in man's mind until it assumes proportions that don't have anything to do with the delicacy or intimacy that God's influence actually has —a characteristic that's emphasized by the tiny figure of the Holy Spirit.

We might call this image of the birds God created in the mind of man, rather than man created in the mind of God.

Men who fall in love with their own wisdom and intellect imagine that they have acquired the properties of divinity; but this is just another product of the imagination, and it assumes the proportions of the ridiculous immediately under the ruthless scrutiny of our artist.

The garden of temptations — which is a far more accurate description of what it is — shows man's mind tempted in all its forms by the external; and the external is represented by the sensual, that is, information brought in through the senses and the body. There is no need to be more specific than this; information and impressions flow into us through our bodies, and it is this intersection between the organic being and life itself, where the question of our temptations arises. The temptations draw us away from the inner; and in each case, we believe in the body, instead of the soul. As in the left-hand panel, it's incarnation itself that creates the dilemma; the consequences, while real, are secondary. We believe that we are attracted to and involved with events outside of us; but in fact, it is the events inside of us that first create the attraction.

This is the significance of the naked men and women; stripped to the bone, and smooth-skinned, like Jacob, everything is internal. They don't have the hairy bodies of Esau, for whom everything was outward.

Far to the right hand side of the painting, one figure indicates the action necessary to negotiate one's way through these temptations. Either a magician, a shaman, or dervish, he bears multiple protections from temptation, and seems to be invulnerable to the scenes around him.

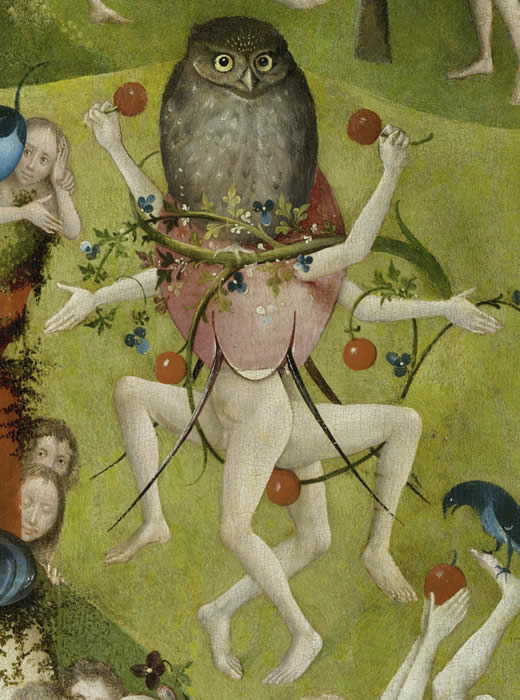

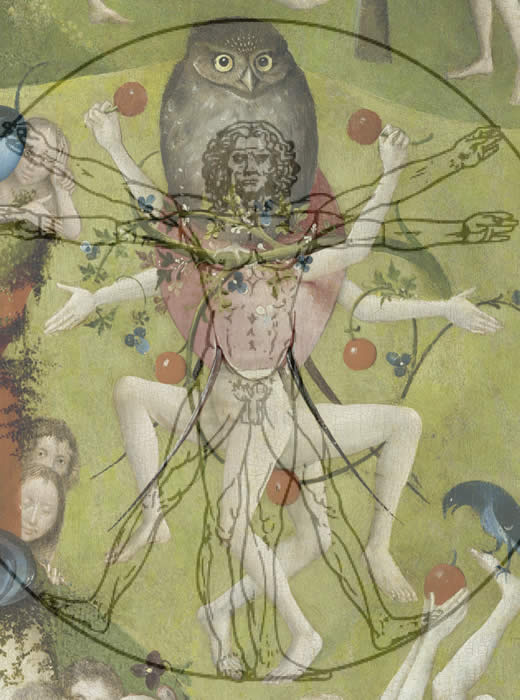

What the artist gives us is clearly the Vetruvian man, in movement. Not static, locked within the confines of a circle that defines him, like the persons in the Tantric Circle to his left. They are trapped in the ordinary wheel of life, from which there is no apparent escape. The dancer stands apart: one who lives outside the circle, who has attained inner freedom.

Leonardo believed the human body to be an analogy for the workings of the universe, and Bosch has invoked his image in a new and extraordinary form, crowned by wisdom, protected by a divine shell, wrapped with the protective living tendrils of God's Grace.

Anyone who doubted the esoteric significance of the scenery in the painting must now rest their eyes on this image and understand that the artist's intention in showing man's relationship to God and the universe was never in question. Here, Bosch announces, is a comprehensive inquiry into the nature of man: Study it with care.

Everything, in fact, in this painting is in constant movement. The image may be static; but the action it depicts is not. It's universal, and constant; everything is engaged in an act of becoming. The panels themselves are engaged in the act of becoming, and the characters in them participate. The flow of both the storyline, the visual symbolism, and the rotation of the Tantric circle itself imply an eternal act of creation. This is in fact the point of the upper portion of the central panel.

This act of creation is not one separate from the entities it creates; the artist has given us a participatory creation, one in which mankind is an active agent in the process of divine influence on the material world. Mountains become organic entities, growing things in their own right; they sprout foliage and sexual organs, procreate. Tiny events take place in overwhelming landscapes, imparting an impression of scale more reminiscent of Chinese painting than European art.

Above all, the artist gives us not a static universe, but one forever in the process of becoming something new.In this process of re-creating the universe, Bosch takes us from the divine to the mundane as effortlessly as he wields his brush, illustrating threads that connect the two on every level. And in the process, he takes us deep in to a lens that magnifies our absorption into our own temptations. We are consumed by the things we feel inside ourselves: they become what feeds us.

What we want to caress and be in relationship with is the lowest part of ourselves like the fish being stroked lovingly in this vignette. We are turned upside down; instead of offering the Lord our highest parts, we offer him our lowest ones. And it's all a childish game of acrobatics; nothing one can take seriously, even though the fate of the soul itself is at stake.

There is more than the illustration of proverbs at play here; this is a grand game, played out on a grand scale.

Influences

Ultimately, this entire painting is about influences, about what influences the inner state of mankind. It begins with a picture of the influence of the divine flowing downwards into earth; and everywhere in the painting, water represents influence, that is, that which flows inwards into man, through him, and then outwards into the world.

The Heavenly or Spiritual state encounters material reality through the vehicle of man's consciousness. The quality of the outer world is dependent on the ability of man's consciousness to perceive Divine, Heavenly, and Spiritual influences, and translate them into the material world. The world in the right-hand panel, which has gone terribly wrong, has gone wrong strictly and solely because these influences have not been properly transmitted. They die; they are slain by man's inattention to the Heavenly or Spiritual qualities of his origins. Hence the word of God, stabbed with a knife and pinned to a blue shield of worldliness. This becomes the leitmotif under which evil slays a man's inner life, pinning him up against the mortuary slab of his own grave, inside of which the pandemonium of his inner life runs riot.

In the right-hand panel, Bosch systematically deploys a veritable army of esoteric symbols in order to get his point across, most of which are easily identifiable and even well known to those who study esoteric questions and observations about the nature of man. Many of them are so obvious that they barely need explanation to serious students of inner evolution; and many of them are covered in detail in the slide shows. Nonetheless, let's review some of them here again.

This image clearly says that we are blind: we don't see ourselves. In addition, our head is not connected to our body — there is no relationship between our inner parts, our centers.

The theme that we can't see what we are is iterated a second time by the blind beggar on top of the instruments of justice.

The chaotic crowd behind the mortuary slab representing the many "I's" in man, invisible to his ordinary self. The repeated images of knives piercing, cutting, and stabbing represent the severing of man from his essence, his true inner nature. He has no inner unity; and he has no awareness of this. The repeated images of death are actually allusions to the idea of death in life, that is, that a man is asleep to himself. Only if he awakens can he live.

Asleep, man becomes prey to forces from the outside world.

They gut him and feed on him.

We can know for certain that this series of images (the crowd, the huntsman) represent a process that takes place inside a man, within life, because Bosch has also provided us with an allegory of what takes place after life in the same panel, rendered in a series of very distinctive grisaille figures that clearly set them apart from the allegory of man's condition within life.

The dead guys, in other words, come later.

Above is but one of these images; taken together, they form a complex story line that includes a transit through purgatory to punishment. See the slideshow on the right panel to follow the whole story.

Viewers interested in truly understanding Bosch's esoteric message must understand that some apparently baffling pictorial devices were very carefully constructed, and quite intentional, so that we would be able to see the difference between one commentary and the next, as well as the connections that link them. This particular set is a good example.

Because he is unable to identify higher, or true, divine influences within himself, man turns to false ones, which deceive him in the name of their own authority.

Because he turns to outer influences rather than inner, or Divine, ones in order to establish his authority, his instruments of justice are perverted machines that carry out a mockery of the process.

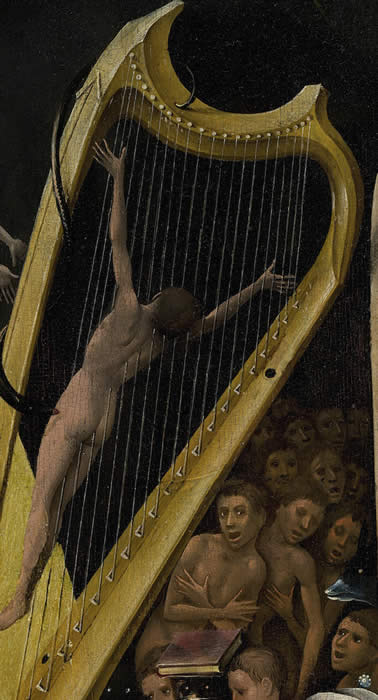

The symphony of human judgment abounds in inner allegory.

Man is played by the strings of his life in the same way that a musician plays his harp; man, in other words, is just an instrument upon which the notes of life are played, not the player. Life is furthermore composed of vibrations, and man is just, like the strings, a vehicle for the transmission of those vibrations. God is, in fact, the musician.

He finds himself pinioned to the instruments of life by the serpent of temptation: it both delivers and binds him to his fate.

In this fallen condition of beggared inner authority, the illusion of Divine understanding (symbolized by the demonic judge, wearing robes of the same pink color as the divine fountain,) spits out pearly lies, whose value is only as great as what's written on a man's ass. He has a pearly diadem on his head, indicating that he not only spits out lies, but is crowned by them.

The entire scene reminds us that we judge ourselves; and that we can only judge ourselves with lies, because we know no other way. Under earthly or outer influences, this is the best we can do.

In a Dantesque scene replete with Ouspenskian overtones, our fallen condition delivers us to be processed automatically, through a machine of falsehood and mechanical action, to our fate: the ravenous beast of our lower being, which devours us. All our outer actions lead us to nothing except excrement. This parable was reminiscent of Gurdjieff's adage to become aware of our own nothingness.

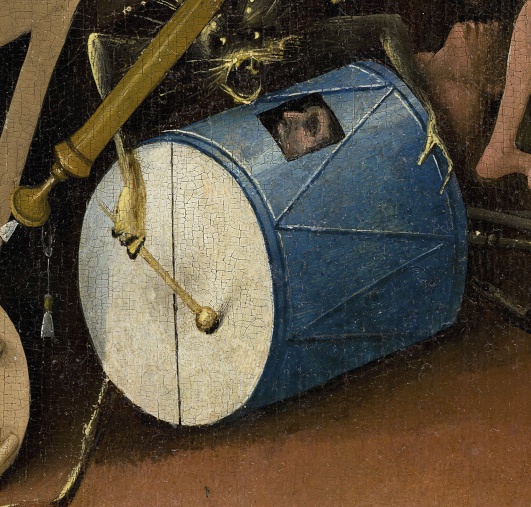

The drum, an empty vessel, is used to make noise; but even with man in it, it is still empty, and can serve its purpose.

We make an enormous amount of noise... we live subjected to the painful inner cacophony of our many selves...

Yet this, in the end, is what it all amounts to.

Our entire being is swallowed by the material, whole, with all good fleeing from us, leaving nothing but shit when the process is done.

Yet take careful note. Bosch leaves us no doubt whatsoever, using his signature technique of color to indicate meaning: the body emerging is not dead— it is alive.

The allegory of death begins with the figures rendered in grisaille.

This is what we are, in life.

Nothing.

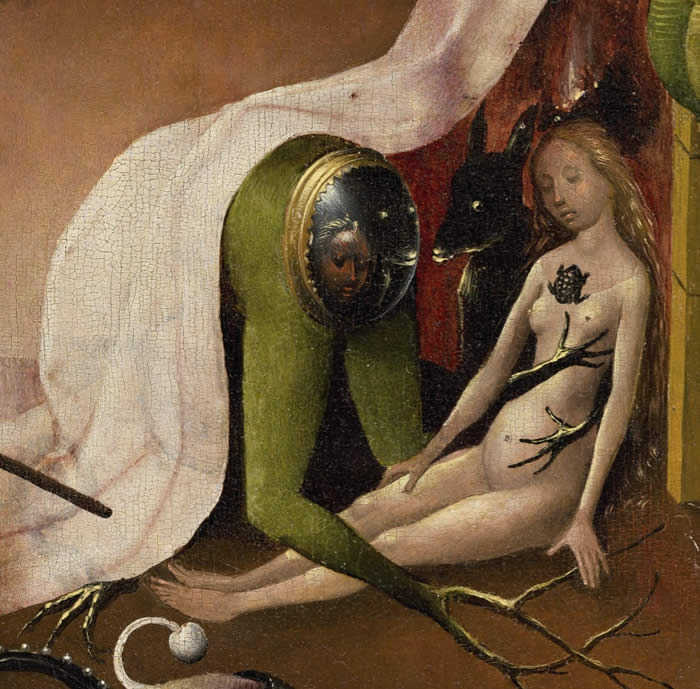

The most sacred feminine part of man — represented in the left-hand panel by Eve, and in the center panel by the virgins in the central pool — puts in a final appearance. She's now asleep, lulled into hypnosis by her own vanity.

These are the parts that ought to be receiving the holy influence of God, but they are now unable Like the earlier metaphorical and symbolic treatments of death, this is a visual parable referring to the unconscious nature of man, who is no longer aware of himself, his place, or higher influences.

In the middle section of the painting, which represents transformation, we encounter the culmination of the esoteric arguments that Bosch wants us to understand. They summarize more precise understanding of the inner nature of man, and are intelligibly couched in the artist's own questions about his nature, which he presented in what is definitely an unprecedented scale.

The ever present question of violence and death, rendered in living flesh tones throughout the rest of the panel, encounters its first transactions with the soul in the form of the grisaille figures that represent the pageant of death. Bosch was careful to delineate the difference between the interactions of man depicted in other parts of the panel and the events in this section, using this technique. The pageant leads us from the right-hand side of the panel on a winding path back to the left, where the souls of the dead are judged. Its purpose is to remind us that death itself is the inevitable end of all human activities. With one or two notable exceptions, from the moment Adam and Eve appear in the Garden of Eden up to this point, only human beings are rendered in flesh tones.

We now leave the living world. We take with us our lower self, symbolized by the fish; and although we may think we wear a warrior's helmet on this journey to the underworld, it somehow reminds us more of a chamber pot. We are naked and helpless. The soul slinks off to its fate as though it already understands the shame it brings with it.

The river Styx is frozen; no boatman is meeting dead souls to take them to the underworld. Bosh doesn't offer us any comforts of the familiar here; we are on our own, with full responsibility both for ourselves and the journey we take.

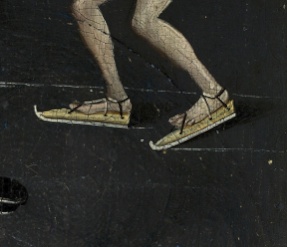

Bosch chooses a peculiar and remarkable device to remind us of our change in state, our insignificance, and our imagination about our ability to act in this vignette of ice-skating. The metaphors he presents work on a number of different levels, the most superficial of which is that we are racing towards an early grave.

What appears to be at first glance a boat or sled is actually a giant skate. The figure to the right, wearing the same skates, has suddenly shrunk. He's now a tiny man on a huge ice skate.

A most peculiar image, the device employs a technique the artist has already used repeatedly: oversized objects represent objects in man's imagination. Here, the skating man indicates a man who thinks that he can do things — that he is the one controlling his movement and the direction he's going in. But his vehicle is imaginary, a figment of his fantasies about his own ability to do things; and he is in fact racing towards his judgment in a process that is out of his control. His tiny size relative to the vehicle that is carrying him represents forces much greater than he is. His fall through the ice reiterates his lack of control over the process, and his failure to understand his own destination.

This image is also a reminder of Gurdjieff's contention that man is subject to mechanical forces, and acts without consciousness. The oversized instruments, cutlery, and key in this panel all represent tools or instruments that man employs to do things; play music, cut things up, open doors. But all of them are larger than man; instead of man being in control of the things he does, the things that he does things with are in control of him.

The realm of death and judgment

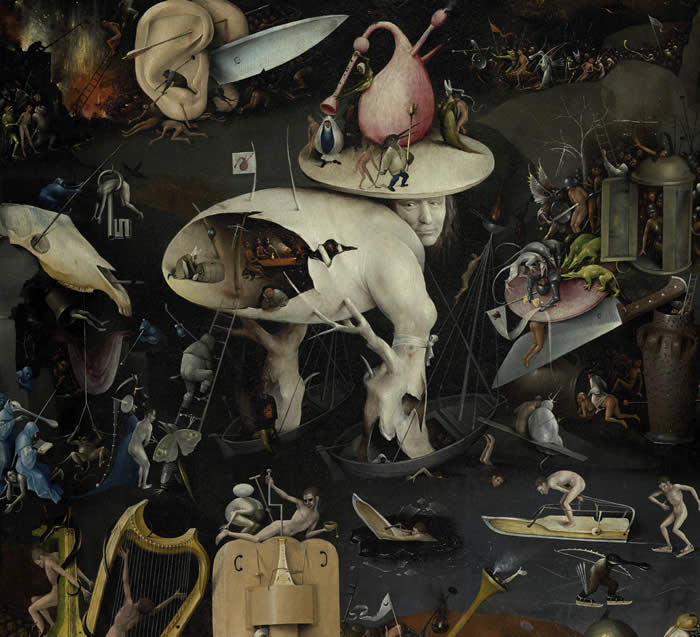

Undoubtedly the most compelling element of the entire painting, and the one containing the most powerful argument for esoteric interpretations of the piece, including man's understanding of his own inner condition.

Individual elements in this are examined in considerable detail in the slideshow for the right panel, so we will not walk through them one by one. The critical element to understanding the action in this panel, which centers around judgment, is to see that the artist has created a sophisticated and entirely unprecedented metaphor for his own inner condition in the huge and objectively bizarre central figure.

Unlike conventional pictorial treatments of judgment in purgatory, which take place on predictably theatrical stages, Bosch has given us an excursion into surrealism, in which the central figure is a man — undoubtedly, in my opinion, the artist himself — contemplating his inner state. His backward directed gaze, resting on the figures who are feasting in his belly, leaves us little doubt as to where his mind is, or what it is usually focused on.

Above him, a merry go round of thought plays itself out, deaf to the divine bagpipes— higher influences — who are desperately trying to send a message to him.

This huge figure, suffused with symbolic inferences of its own mortality, pierced by thorns of its own flesh, ignorant of both its own fallen state and of the divine, poses one question after another about who we are, what we are thinking of, and where we are going. The action in the painting, which has so far taken place on a vast, cosmologically sophisticated and metaphysical scale, comes home to roost in the body itself, and the relationship to it. The egg, which has accompanied actions through the painting that develop it as a vessel which contains what the soul acquires during life, reaches its maturity here and is broken open to reveal what man's preoccupations are; what his essence, the summary of his inner contents, is.

Our denizen of purgatory, by his own estimation, has preoccupied himself with the things of life, not an attention to his divine nature — which is perpetually trying to reach him, but unable to do so over his distractions. He finds himself in the midst of chaos, all of it destructive.

Yet the numerous humorous devices (see the slideshow) along with the wry smile of the artist, which has a Mona Lisa-like quality (and the paintings, oddly, are very nearly contemporary) suggest that the artist, engaging in this sleight-of-hand introspection, this nearly impossible juggling act of symbolism, understands his limitations. There is a knowingness in this scene, an acknowledgment: a willingness to see what we are, rather than look away. The subject may not understand what is happening to him, or see, within the context of the painting, where he is or what is happening; but the actual artist, the second self — the real Self, not the image or artifice of the self — does see, and gives us the truth in the art itself.

There is a complex and intelligent philosophical game being played out here; one that works on multiple levels, and one that asks questions the viewer must return to again and again in order to discover the question of relationship between the parts. It's true, in the gross analysis of the painting, that the 400 figures represent mankind; but taken together, from another point of view, they all represent one man — ourselves — or, the overall state of "man" in general.

Bosch evidently had a sense of humor about the nature of inner inquiry — as every real master of inner work must. He was clever enough to give us an overwhelmingly negative, nearly disastrous and horrific portrait of ourselves in the right-hand panel, yet parse it out by making it funny; and advising us that, while it is true we are nothing, we should not take ourselves too seriously. A lightness is necessary in self-awareness; despite the condemnation of man's inner state, Bosch is not advising us to wear hair shirts or engage in flagellation.

The central figure in the right-hand panel, above all, is an observer: one who sees.

And so, in the end, the artist seems to be advising us to look, to see, to take in what we are, and to understand. Despite the visions of hell, there is an almost compassionate element at work here; and so, despite the disaster, we are left with a feeling — paradoxically — of hope.

Both da Vinci and Bosch were masters of penetrating beyond the surface of things to reveal an inner quality, a question about man and his nature. Each one was completely extraordinary, and they stood well apart from the other artistic figures of their times. The fact that they produced completely different kinds of art is hardly the point; the point is that the art of seeing into men, conducting a visual inquiry into the nature of their soul, can be as essential as any written philosophical treatise.

A Doremishock resource

Contact

![]() a doremishock resource

a doremishock resource

All material copyright 2013 by Lee van Laer. This work may not be reproduced without permission.