Levels: a Critical Key to Understanding Cosmology

in Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights

While the subject of levels is covered at some length in the slide show essay on symbolism, some additional commentary will shed light on the importance of this idea relative to esoteric philosophy on the matter.

Both the Garden of Earthly Delights and The Haywain share a distinctive cosmological structure indicating levels, and the influence of a higher level on a lower one. The device is also employed in several other pieces. The idea that the universe is structured in this manner is an ancient one; but a new flowering of religious cosmologies which arguably reached its pinnacle in the 13th century with Meister Eckhart and the Islamic texts of Ibn 'Arabi left a profound mark on European societies, reinforming religious understanding in the process.

Dante's Divine comedy, another major work of the times with a definitive structure of levels, may well have drawn inspiration from the Sufi doctrines, as argued by some scholars. In any event, the idea of divine influences both forming and informing the earthly sphere were well-established several centuries before this painting emerged from the esoteric schools in middle Europe.

It should, in fact, be unsurprising to see such devices in a painting, especially one produced by an individual so clearly capable of works of genius and the imagination. Bosch was clearly a well-educated man, with a decisive grasp of religious and spiritual issues. He came from a town with a major gothic cathedral; it was a major religious center and sat at the confluence of deep, longstanding traditions in worship, philosophy, and fine craftsmanship that informed the arts. He was also a member of the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, a society that venerated the Virgin. We can thus presume that he had access to a level of religious society sufficient to have been exposed to doctrines of this nature. His paintings indicate that this was no ordinary social organization, but a true esoteric school.

The imagination plays a central role in both Eckhart's and Ibn 'Arabi's understanding of how one must conceive of and approach God. Bosch takes this concept and lays it out in spades; the entire work is a tour de force visualization of heavenly and earthly influences, with the collision and subsequent transformation laid out in an elaborate pageant.

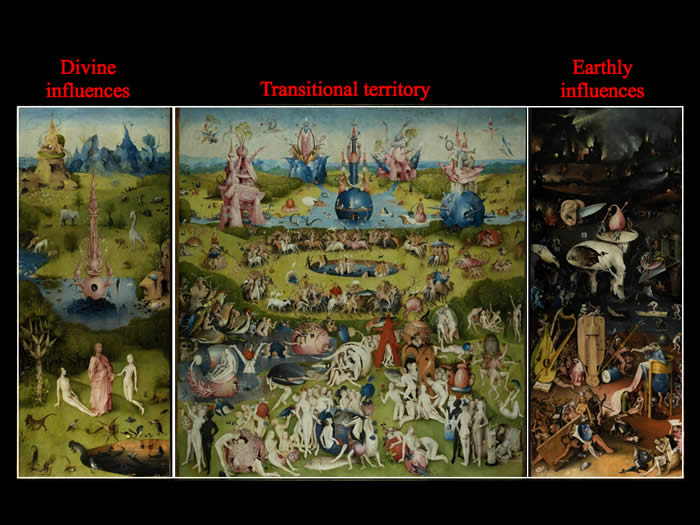

The painting is constructed so that influences of a metaphysical or higher nature are seen at the top of the painting. The middle ground, what we will call the ground of transformation, at the center of the painting, depicts — in all three panels — the territory of interaction and change, where the higher influences the lower. And, in all three panels, the earthly sphere is represented at the bottom of the painting.

Understanding this question from the point of view of influences of the spiritual, or heavenly, from the inner life of man which move towards the material, or natural, outer life of man, the same structure applies. In esotericism, the highest level of influences is the esoteric, or inner influence. This is the influence which ought to come from the Divine Spark of God, as shown in the left-hand panel.

The intermediate level of influences is the mesoteric, or middle, level. And the lower level of influences is the exoteric, or outer level.

The artist actually created a second matrix of this architecture, so that the painting also reads the same way from left to right.

As a result, the visual formula of influences is cruciform, indicating, conceptually, both a vertical and a horizontal level — an incredibly sophisticated metaphysical cross, conceptually embedded in the painting by employing the framework of movement of influences both top to bottom, and left to right.

It is really a quite staggering achievement, once one realizes what the artist accomplished. No other painting of its time even really came close to this level of philosophical discourse, which is not presented literally, but rather buried in the visual architecture of the painting itself. One has to think about the painting to understand just what Bosch achieved; and the painting was not just to marvel at, but to think about. He made certain there was plenty of material to ponder when he created it.

The entire painting is, in essence, a visual inquiry into what influences humanity comes under. The left-hand panel represents the essence of man, which stands next to and can come under divine influences; the right-hand panel represents personality, which is under earthly ones. The center panel represents the middle ground, an area of conscious action were a man must understand the influences acting on him and make choices.

In later centuries, Swedenborg would describe the process of the higher influencing the lower as Heavenly inflow in his equally extraordinary book, Heaven and Hell; and G. I. Gurdjieff would speak to his pupil P. D. Ouspensky of influences A, B, and C, meaning lower, intermediate, and higher. Influences see were understood to flow into earth directly from the highest level of the Divine, as they do in the left-hand panel of the Garden of Earthly Delights. The left-hand panel is in fact an exact replica of Gurdjieff's cosmological premise: influences C flowing into the natural world. Although Swedenborg, Gurdjieff, and other meta-physicists arrived much later in time, the concepts were already well-known in Bosch's time, and he employed them specifically, and in an unabashedly mystical way, by using the pink tower of God's influence to give us an idea of the mystery surrounding the inflow of the divine.

This magnificent structure, definitively mystical and without any doubt one of the most extraordinary images of its own time, or perhaps any time, is to the discerning viewer conclusive evidence of Bosch's refined understandings on this matter.

Everything about the painting, in fact, ultimately revolves around levels, the inflow of the divine, and how its contact with the material sphere affects it. It was, in all likelihood, inspired by mystical visions and an inner revelation; no artist could have achieved this level of discourse on spiritual matters without such an insight.

A Doremishock resource

Contact

All material copyright 2013 by Lee van Laer. This work may not be reproduced without permission.