The Adoration: The Background

One of the ways one can be reasonably certain that Bosch painted a particular painting is by the level of intention in it, that is, how much the details encode.

In order to explain this more thoroughly, we can compare the background of this painting to the background of a comparable and extremely fine painting by Rogier van der Weyden, which is currently located in the Boston Museum of fine arts.

This is a painting of Saint Luke drawing the Virgin Mary, painted between 1435 and 1440. It's an exquisite example of Northern Renaissance painting; and it predates the Hieronymus Bosch piece by approximately 35 years. Like most Renaissance paintings, along with the lavishly clad figures (wearing textiles that would have cost a pretty penny in any era), it features an architectural foreground, allowing the artist to display his skill with perspective and stonework; and as is always the convention, a background with an elaborate landscape, buildings, water, and sky.

The piece is one of the consummate masterpieces of the Northern Renaissance; yet we see that there is little or no real storytelling content in the painting. It's all about the mastery of technique — and mastery there is. But the foreground is more or less one-dimensional in its symbolic content; and when we get to the background of the painting, it, too, is barren ground for introspection.

All we have here is a conventional scene from an ordinary town; a woman carrying water, a couple strolling, a man on horseback. Rather than give us a story that integrates with the foreground, a lesson in the inner search we engage in, the artist has given us what amounts to stock photography for his era.

With Bosch, who took a great deal of care to put an intention in nearly every element of his painting, we encounter a very different story. The Adoration of the Magi has a background rich in allegory and symbolism.

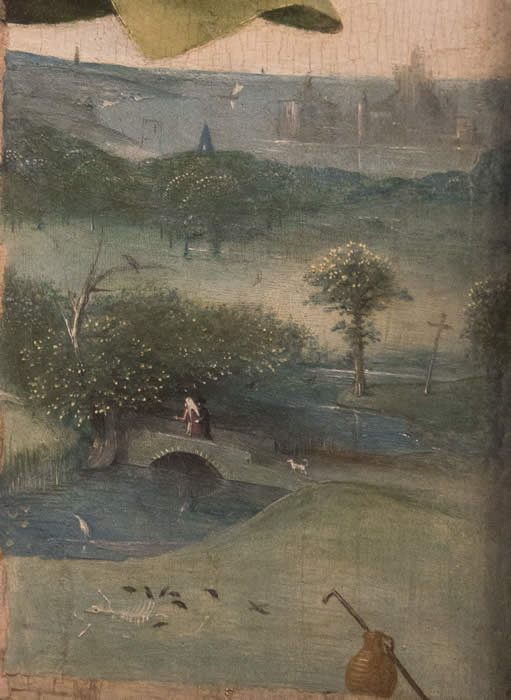

In the distant background lies the motif of a mystical city representing the New Jerusalem.

We know the city is meant to represent a unique city because of the massive scale of the cathedrals, especially the one to the right. Both spires eclipse the size of the city gates, implying architecture on a scale that well exceeds the engineering capabilities of Bosch's times.

Although the countryside is pastoral, armies are still in action, patrolling, ever vigilant against the forces of evil.

These armies, however, are not just any armies. On the left, we have the soldiers of Christ, signified by the two white hounds leading the cohort. Behind them looms a cross on a tripod. Next to the tree on the far left, a small figure in pink indicates that this army is under holy influence, possibly even led by Christ himself.

On the right, Muslim troops are led by a sheikh in a white turban. The struggle is, in other words, a recapitulation of the Crusades — the struggle against the Muslim heresy. But it is, as well, a battle between good and evil, between virtue and lust — lust as signified by the red flag carried by the Muslim troops.

In front of this scene of grim portent, we have a miniature allegory. A man puts down his walking stick, which doubles, perhaps, as a shepherd's crook; and he takes a woman's hand. She, too, is dressed in red, in a deft allegorical gesture quite familiar to us if we study Bosch carefully.

To our right, which is his left — the sinister side, the side that tempts us always — a piper plays a tune beneath a flowering tree. Who could resist the temptation? Music, a beautiful woman — the next thing you know, they are arm in arm. The walking stick, or crook, which was picked up and brought along, is becoming an afterthought. The man no longer tends his flock, which wanders aimlessly in the distance.

Even the tree the piper sits under is depicted with a rotten trunk, a hole lurking at its base. This refers to the hollowness, the insubstantial nature — yes, perhaps, even the corruption — of what looks so alluring and beautiful.

Next to it slumbers a dog; the creature that ought to be vigilant, ought to be watching, is fast asleep. The allegory is practically Sufi in its references — all of it rendered in tiny characters that mean almost nothing, at first glance, relative to the whole story, even though they are in fact an essential part of it.

In the right hand side of the landscape, the two, now lovers, stroll across a bridge, indicating the virtues of heavenly love. Like many of Bosch's vignettes from the Garden, tossed off almost effortlessly as adjuncts to his central theme, this touching image is a whole painting in itself. Note the cross on the right, indicating Christ's presence as a natural element of the landscape. It's tiny details like this that remind us of how thoroughly Bosch attended to his works.

|

||||||

| There is much more to this scene, however, than meets the eye. | ||||||

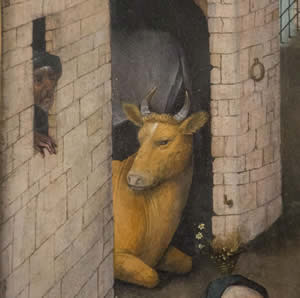

In order to fully appreciate what's going on here, we need to be reminded of two elements found in the tantric circle of the foreground: first, the white hound, who symbolizes the vigilant pursuit of Christ, one's spiritual quest; and second, the bull—representing the evangelist Luke, purification, and personal sacrifice.

These two creatures appear again in the vignette of the lovers crossing the bridge. First, the bull, lying on the ground, his bones picked clean by crows:

Second, the hound who seeks Christ, left behind forlorn as the couple crosses the bridge:

To put in all in context, we need to see how the couple is crossing a body of water, going away from the bull; away from the dog; away from the cross:

They are abandoning any thought of a spiritual quest and marching away from the ox, the hound that seeks Christ, the cross — into a copse of trees, once again, flowering trees, like the ones on the left-hand side that originally tempted them.

In the foreground, the pentitent traveler's stick and jug of water are abandoned once and for all— yet in the figures in the first position of the tantric circle, representing youth and old age, the penitent youth retains his walking-stick:

We ought here to be reminded of the way Bosch employed a consistent symbolic language from painting to painting: the stick is essentially the same walking stick the wayfarer used:

The lesson here is clear enough. The walking-stick represents both the seeker's inward intention and outward aim: to find God. In the background of the adoration, on the right hand side of the painting, which is the natural side of the circle—the side representing ordinary life, of which the three kings are still, like all the other elements, a part— life takes over. The man forgets his spiritual search; he takes a wife, and he walks into the flowering tree.

The couple has, in a nutshell, done something Gurdjieff would be familiar with: they have forgotten themselves.

Even the tree is not what it seems. Although it is rich in flowers, over it looms a dead branch — an ominous portent. On it lurks what looks like a vulture.

And although the landscape leads through another copse of lovely trees, and a church — suggesting a wedding — the path before the couple ends with a gallows.

This isn't an accident. Bosch has managed, in the seemingly insignificant background of this painting, to create an elaborate allegory of the path for those who forget the spiritual life. Yes, they get the rewards of love and marriage; yet death always looms over all of us, no matter how beautiful the landscape of the future we paint in our minds is.

It's equally worthwhile to contemplate, for a moment, the way Bosch has created a powerful center of gravity in Mary and the Christ child, around which all the major figures in the painting circle. Everything else lies out of their orbit; they form a solar system of their own, with the figures in the background nothing more than streaks of light from the comet of life, which lasts but a brief moment.

Comparison of the two paintings reveals just how carefully Bosch constructed his works. Other artists of his era used little or none of the symbolism he so richly employed; and by comparison, many of the paintings which purport to be of spiritual subjects are, in the end, mere decoration, although it is true that many of them reached the heights of the very finest decoration.

What Bosch was up to was something else. Every element in his paintings calls us to remember who we are and where we are going. In this, he surpassed his contemporaries, and continues to engage us hundreds of years later.

|

||||||