On Bosch and Gurdjieff

When I was nine years old, my parents took me to the Prado in Madrid, where I first saw the work (The Garden of Earthly Delights) in person. Absolutely stunned by its imagery, I spent over an hour in front of it. As a matter of fact, this piece of art is definitely what launched my inner search for Self, although I didn't exactly know that was what it was called when the painting fell deep into me as an impression, and began to work on my psyche in mysterious ways. It began, in my essence, a process of questioning: what does life mean? Even at the age of nine, I could see, we don't understand that.

This artwork made that question a living thing inside me.

Above all, the painting represents a challenge to what we believe to be true. And those with the patience to go through all of my commentaries will understand why I say that. Some claim that it's not possible to interpret all of the symbolic elements in a coherent environment and timeline, but that is patently untrue, as I prove in my commentaries. This painting represents a single, whole thought — not a series of disjointed images. The trick is that one has to understand the overall thrust of esoteric philosophy in general in order to understand its message, which has a universal meaning pertaining to our inner lives.

Art critics, historians, and academics don't study these questions, so of course for centuries they have been unable to interpret the painting properly. In terms of explanation, it probably would have fared better had students of metaphysics and philosophy tackled it much sooner.

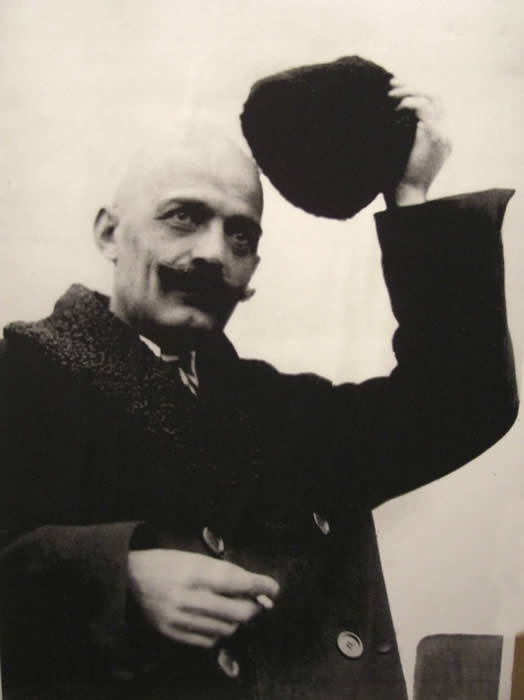

Here's the background story: Last Christmas Eve, in an unexpected epiphany, it suddenly struck me that the painting bears an unexpectedly close relationship to Gurdjieff's magnum opus, Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson.

This impression entered me in my deepest parts, of an instant, and I knew at once that the question deserved much closer investigation. The result is my extensive analysis of the painting, including a detailed examination of the symbolism the artist employed.

The two works have similar aims; each employs an elaborate, unexpected, and challenging approach to convey their message. Above all, both works display an intense intentionality; each is a work of sheer genius that required the creation of an internally consistent world of its own. And each is of course not only a tour de force of esoteric lore; each is rightly regarded as a unique masterpiece with few, if any, precedents.

Gurdjieff's stated intention, in the book, was to "to destroy, mercilessly and without any compromise whatever, in the mentation and feelings of the reader, the beliefs and views, by centuries rooted in him, about everything existing in the world." When I first saw The Garden of Earthly Delights, it produced just such an effect in me: nothing in it was as I expected anything to be. Everything was mysterious; and, evidently, it was about what goes on inside of us. Although the images are externalized, the actions are about our inner life and its consequences.

The painting takes the form of great religious art from many cultures, notably the stained glass of cathedrals, and Tantric Buddhist and Hindu art, with their exuberant color palettes and over-the-top imagery. Typically, the most intense religious art forms hallucinogenic landscapes, brightly colored vistas populated by a vast range of improbable deities. Such artwork mimics the type of experience induced by chemicals such as LSD; but, more importantly, it also reflects the action produced by what yoga schools call Prana, a higher force of life, which, when it is active, can produce visions of this kind without any ingestion of drugs whatsoever.

Prana, in other words, can induce a bridge in man that inspires a different understanding of the world; in the case of painting, it is visual, but Gurdjieff gives us the literary equivalent, in a book as elaborate and extraordinary as any group of Tantric paintings or iconographic representations of Biblical stories.

The triptych, when closed, shows us the earth in its primeval state, without any animals. It is a picture of essence: pure, unmapped territory, without any actively conscious beings to imprint their presence on it. A perfect tranquility prevails. Only when one opens the altarpiece is the action that takes place within this wholly prepared world revealed.

In the absence of any definitive interpretation of this painting, we are left to our own devices. The painting becomes a mirror of what we understand; and the obscurity of its images and subject matter allow us both the latitude and the longitude to create our own world of interpretation; a world that must of necessity reach down into the subterranean levels of our own consciousness, in the same way that Gurdjieff advised us his book would. It can be argued, in fact, that the intention of the painting is to serve a similar function; an iconic reformulation of our psyche, undertaken from the ground up.

A thorough analysis of the painting reveals a rich, dense world of symbolic allusion that certainly bears comparison with the enormously complex allegory of Gurdjieff's Beelzebub. Each work represents an abstract of man's inner world; each one recapitulates a fall from Grace, with a critique on man's behavior. Bosch, it's true, may not offer us any remedies, as Gurdjieff does; but they are implied, if not explicit. One might say they are built in by inference alone to the challenges he presents us with in his extraordinary visual narrative.

Each of these works emerges into the world from an equally mysterious and magical place of origin; they share, in other words, a common esoteric parentage. Each sinks into deep, secret places in the psyche of those who encounter them; and the effect is transformational, as their images, symbols and questions go to work beneath the conscious mind, undermining our assumptions about the world, and calling us to an ongoing examination of our Being.

There are few such works in the world; and they are very great gifts to us, indeed.

This brings us to one further note.

The reason that Bosch is the least known of all the greatest Northern Renaissance painters is that he was a member of an esoteric school, and not interested in public notoriety. His major paintings were inner teachings, not works to aggrandize the ego or objects of art appreciation.

Men of this kind are prone to stay out of the public eye.

I'm currently at work on commentaries on The Haywain, Bosch's companion piece, which depicts the outer life of man. The two paintings are intimately linked, share common visual architecture and symbolism, and form a symmetrical pair of story lines about man's nature. When completed, the commentaries will fully explain Bosch's aim and intention in painting the two pieces, which were originally meant to go together.

This commentary on Bosch's painting and its relationship to the Gurdjieff work was originally published in the Zen, Yoga, Gurdjieff Blog January 11, 2013.

A Doremishock resource

Contact

All material copyright 2013 by Lee van Laer. This work may not be reproduced without permission.